By Sean Kimmons Army News Service

FORT GREELY, Alaska, Oct. 11, 2017 — A small, remote Alaskan

post bordered by mountains and moose herds, Fort Greely is America's major line

of defense against long-range enemy rockets.

Inside its heavily guarded missile defense complex, rows of

ground-based interceptor missiles tucked away in underground silos and radars

dot the landscape. Within minutes, the missiles can blast off into space to

collide with and destroy warheads speeding toward U.S. soil.

Using data from sea-, land- and space-based sensors,

soldiers of the 49th Missile Defense Battalion can spot a rocket launch from

anywhere in the world. If an attack occurs, the 100th Missile Defense Brigade

in Colorado Springs, Colorado, would then relay permission for the battalion to

fire.

A number of recent rocket launches have originated from

North Korea, which has threatened it could strike the U.S. with an

intercontinental ballistic missile -- a powerful rocket capable of hitting a

target with a nuclear weapon. Despite the new threats, Army Lt. Col. Orlando

Ortega, the battalion commander, said his well-trained Alaskan National Guard

unit operates in a constant state of readiness.

"We've always been ready," he said. "Nothing

really has changed from what we did a year ago. We were ready then and we're

ready now."

Still, North Korea has kept the soldiers busy.

Ever-Ready

The battalion has missile defense crew members who work

12-hour shifts around the clock so they can immediately react if a foreign

country launches a rocket.

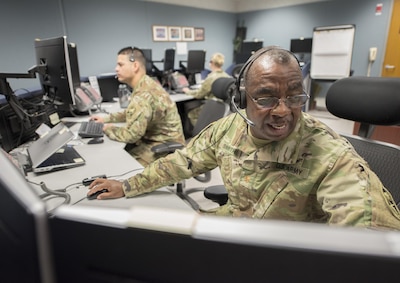

A five-person crew will staff a fire control node at all

times. There, soldiers have several computers, monitors and communication

equipment to stay informed or relay any new developments. It's also where

soldiers can launch an interceptor missile to defeat an enemy rocket, if

approved to do so.

By the end of the year, the U.S. military is expected to add

eight more interceptors to its arsenal for a total of 44. The vast majority --

40 -- will be based at Fort Greely and the rest at Vandenberg Air Force Base,

California.

At Greely, crews train constantly in case they have to fire

one or more of the missiles. Such training can include practicing real-life

scenarios or learning complex software systems. Those skills are then tested by

internal and external evaluations.

"We will do everything we can to get to the top of our

game and maintain that level of proficiency at all times," said Army Maj.

Bernard Smith, director of the Alpha crew.

Team building is also paramount for soldiers because of the

consequences of failing to work as a crew. While confined together in a

one-room node, the bond among crew members can grow strong.

With a diverse team of skilled soldiers from Alaska to

Puerto Rico, Smith said, his crew is supportive and will often teach each other

new things during shifts.

"I'm not very stressed when I come into work because I

trust my crew -- we are a family," Smith, 50, said. "If there are any

issues or problems, they know we can come together as a crew, as a family, and

accomplish anything."

Arctic Living

One of the major's crew members, Army Capt. Gilberto Ortiz,

described the battalion -- made up of soldiers on Active Guard Reserve status

-- as a brotherhood.

About eight years ago, Ortiz left the warm climate of Puerto

Rico for the arctic cold to protect the complex from intruders as a military

police officer. When he heard of the missile defense crews, he decided to

switch careers.

"It was something new [to me], something I didn't know

about," said Ortiz, 32, who is now the crew's battle analyst. "I was

like, 'OK, I'll do it. I'm up for the challenge.'"

Before coming on board, his first challenge when he arrived

at Fort Greely was battling the weather, which can drop down to 60 below in the

winter. He learned how to wear layers, he said, and eventually acclimatized to

the cold. He even earned the "Arctic" uniform tab after he graduated

from the nearby Northern Warfare Training Center, which tests the cold-weather

skills of soldiers.

"The longer you stay here, the more you feel you are at

home," said Ortiz, who lives with his wife and two children at Fort

Greely. "[My] true home is thousands of miles away, but for me this is my

second home."

When she landed her assignment in Alaska, Sgt. Bethany

Hendren was eager to leave Missouri and head up north.

"I fell in love with Alaska before I got here, because

I love to travel and go to new places," Hendren, 29, said.

Similar to Ortiz, the sergeant was originally an MP and

chose to change career fields while at Fort Greely. She now works as the crew's

communications operator, where she monitors and reports all radio traffic on

the ground-based fire control system. While off-duty, she has another mission

to help serve fellow soldiers as the local president of the Better

Opportunities for Single Soldiers program.

Being isolated in Alaska -- which only has a few hours of

sunlight during the winter -- can sometimes impact a person's well-being. So,

Herndon reaches out to soldiers and invites them to events, where they can be

more active and social.

"It is an austere environment, and the winter months

can be quite demanding at times," she said, "but I offer different

programs and events for soldiers to be involved in and to get out there and see

Alaska."

Self-Sustaining Base

Fort Greely's infrastructure was made to be resilient, too.

The post is self-sustaining with its own water supply and power plant, so

operations won't be affected if electricity is cut to surrounding areas.

Security measures and sophisticated sensors can pick up any

movement around the complex. Even when a moose or another animal triggers a

sensor, MPs will always check it out.

"We take anything that comes in as a possible

intrusion," Ortega said, "and we will have eyes on it physically and

with cameras to ensure that it is not someone trying to come on."

All of these precautions go into being able to complete an

incredibly difficult mission, where even the slightest miscalculation can

result in failure.

Once an interceptor is launched, it releases a kill vehicle

that travels roughly 15,000 mph in space and is maneuvered to collide with an

enemy warhead.

"It is extremely hard to hit a bullet with a

bullet," Ortega said.

The Missile Defense Agency tests interceptors out of

Vandenberg. While there have been past successful hits on targets in space,

several interceptors can be fired at the same time, if necessary, to ensure an

enemy warhead is shot down.

'We're the Shield'

"We have confidence in the missiles and the

capability," Ortega said, "but we will ensure with 100-percent

confidence that it is destroyed." That's a promise the entire battalion

must keep, since over 320 million Americans depend on it.

As the lowest-ranking member of her crew, Herndon -- just

like the other soldiers -- has embraced the huge responsibility of defeating a

warhead if the time comes.

"We don't want Los Angeles or Seattle or any other part

of our country to be attacked. It's as simple as that," she said.

"Of course we have our offense ready to go as well, but

we're the only defense out there that can actually stop and prevent it from

coming into our country," she added. "We're the shield."