March 19, 2021

GREG POLLOCK: Good morning, all. My name is Greg Pollock, and I am currently serving as the secretary of defense chair on the National War College faculty. It's my great pleasure to introduce our speaker today, the Honorable Dr. Kathleen Hicks, who was sworn in as the 35th deputy secretary of defense on February 9th, 2021.

Prior to her nomination as deputy secretary, Dr. Hicks was the senior vice president, Henry A. Kissinger chair, and director of the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Her confirmation as the deputy secretary is something of a homecoming for Dr. Hicks, as she has served two prior stints at the Pentagon, including in a series of senior roles from 2009 to 2013. She was previously confirmed by the Senate in 2012 as the principal deputy undersecretary of defense for policy.

Deputy Secretary Hicks began her remarkable national defense career as a civil servant in the Office of the Secretary of Defense in 1993. She served in a variety of positions over 13 years, ultimately rising from presidential management intern to the senior executive service.

Dr. Hicks holds a Ph.D. in political science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a master's from the University of Maryland's School of Public Affairs, and a bachelor's degree from Mount Holyoke College.

Welcome back to the War College, Dr. Hicks. On behalf of all the faculty and students, I thank you so much for being here today, and the floor is yours.

DEPUTY SECRETARY OF DEFENSE KATHLEEN HICKS: Great, thank you, Greg, for that very kind introduction, and it is such a privilege for me to have the opportunity to meet with the National War College Class of 2021.

Over the course of my career, I've had numerous occasions to come and speak with students at National Defense University, including at the War College, and I always enjoy the chance to interact with you, as well as to have the opportunity that this venue provides for me to sharpen my own thinking.

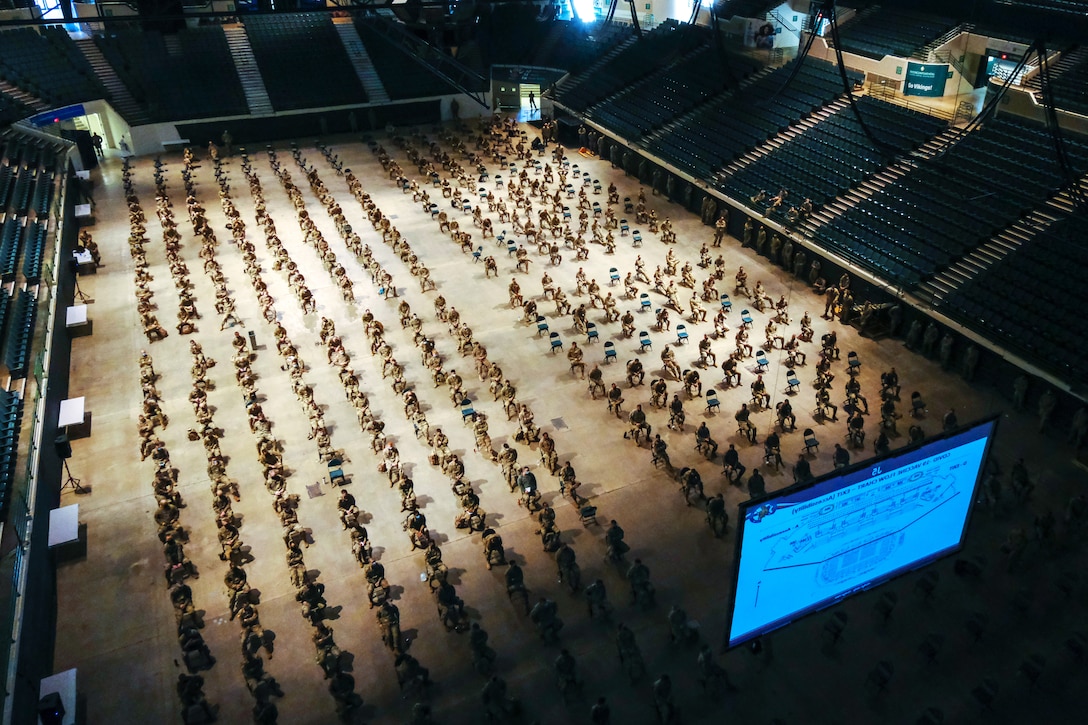

I very much wish we could be together in person this year. I know that the COVID-19 pandemic has substantially altered the War College experience, as it has changed virtually every aspect of our lives, and certainly, of the department's operations.

I hope that you've nevertheless been able to engage the faculty and resources this year to step back from the tactical and operational aspects of your careers and deepen your thinking about the many opportunities and challenges facing all of us in the years and decades ahead.

But before I begin, I want to say that my heart is also with our Asian-American community following this week's horrific violence. All Americans share an obligation to stand up against hate in our communities, and at the Department of Defense we will lead by example in ensuring that every member of our force feels safe, respected, and valued.

This morning, I want to provide several minutes of opening remarks, but reserve the majority of our time together for a discussion with the students, and I'll be happy at that time to answer some questions from all of you.

I want to speak to you today about the decisions we are making and actions that we are undertaking at the Department of Defense to continue to sustain our technological and innovation edge over our military competitors. And because Secretary Austin and I believe that the PRC is the pacing challenge for the United States military, I will speak with a particular focus on it.

Strategic competition is a defining feature of the 21st century. This competition was not preordained or inevitable, but it was certainly predictable. In its 1997 Quadrennial Defense Review, the Defense Department opined that the United States is the world's only superpower today, and it is expected to remain so throughout the 1997-to-2015 period. But, it continued, in the period beyond 2015, there is the possibility that a regional great power or global peer competitor may emerge. The document then explicitly called out Russia and China as having the potential to be such competitors.

Over the past several decades and across multiple administrations, the economic security and governance differences between the United States and the People's Republic of China have come into sharper focus. During the Obama administration, the department joined with the rest of the national security community in undertaking a rebalance or pivot to Asia. More recently, the 2018 National Defense Strategy and the 2019 Commission on the National Defense Strategy, of which I was a member, highlighted the growth of the People's Liberation Army's capabilities and helped crystallize a bipartisan consensus around the defense challenge.

Beijing has demonstrated increased military competence and a willingness to take risks, and it has adopted a more coercive and aggressive approach to the Indo-Pacific region. In 2020 alone, over a host of issues, Beijing escalated tensions between itself and a number of its neighbors, including Australia, Japan, Vietnam and the Philippines. It was involved in an armed confrontation with India along the line of actual control which resulted in the loss of life on both sides and further tightened its grip on Hong Kong, including by instituting an oppressive national security law. The PRC's actions constitute a threat to regional peace and stability, and to the rules-based international order on which our security and prosperity and those of our allies depend.

Against this backdrop, President Biden recently released his interim National Security Strategic Guidance, which highlights the PRC's increasing assertiveness. The interim guidance notes that Beijing is the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system.

To advance the interests of the American people and our democracy, the United States must be able to compete for the future of our way of life across all these dimensions. For the United States military, that will often mean serving as a supporting player to diplomatic, economic, and other soft power tools.

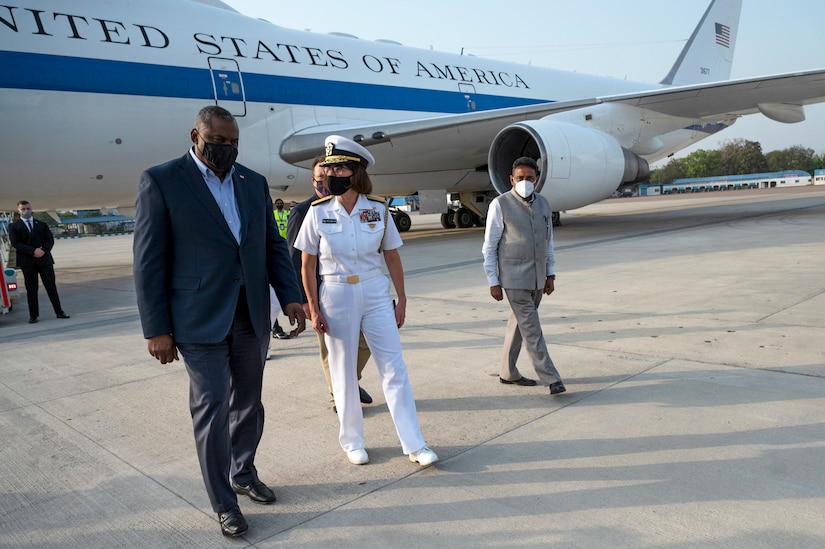

But it will also require the U.S. to demonstrate the will and capability to credibly deter PRC aggression. As Secretary Austin said earlier this week, during his visit to Japan, the U.S. Military, along with its allies and partners, must have the capability to outmatch the PLA.

As the deputy secretary of defense, I am particularly focused on helping Secretary Austin ensure that DOD strategy is connected to its resources. That connection runs directly and significantly through concepts and capabilities. We must invest ourselves not only financially, but also culturally in major change if we are to exploit our advantages and close critical gaps to deter determined adversaries.

And I am confident that we are pos -- poised -- excuse me -- to do so for a number of reasons. First, is his message to the force, Secretary Austin made clear that DOD is committed to both innovation and modernization. We will have a commitment to rapid experimentation, which provides the needed space to test and refine innovative operational concepts.

On the path to disruption, learning happens partly through failure, but we will seek always to act with the trust of American taxpayers in mind, and at reasonable risk.

Simply developing concepts and testing theories will not be enough. We will also be committed to bridging the so-called valley of death, ensuring we actually field needed capabilities in the force. Making room for new capabilities will require difficult choices. Where the nation's security needs are no longer being met, the department will work closely with Congress to phase out systems and approaches optimized for an earlier era.

We will also be attentive to making adjustments in the incentives that drive how we invest, select talent, and innovate. We will be asking fundamental questions, like how do civilian and military promotions encourage a culture of innovation? Do we have the right skillsets in our future force, and can we attract the nation's best talent in the coming decade?

How can we, DOD, be a more reliable and agile partner and customer? How do we secure our supply chains and ensure we have access to critical technology? What transition approaches might be helpful to defense communities and our industrial base, as we shift to future technologies?

And how does our global force management approach protect future readiness and preserve states now for experimentation and exercises that advance our operational art?

Secretary Austin and I are determined to work with military and civilian leaders in the department, and with key partners in the interagency, on Capitol Hill, and in the private and research sectors to get after these questions.

A second reason I am confident we can deter adversaries effectively is this administration's commitment to strengthening perhaps the United States' greatest asymmetric advantage, our alliances and partnerships.

The ability of the United States to pursue common economic and security goals with other nations is the cornerstone of our success, which is why rivals are attempting actively to undermine trust in us.

For the U.S. military specifically, our defense relationships and the networks between and among them strengthen interoperability, generate common norms and respect for responsible international behavior across domains, and deepen the agility of our collective global posture.

Third, the secretary and I know that meeting our greatest challenges and advancing the department's priorities will require sustained senior-level attention to the levers that create lasting institutional change. Fundamental to our approach is the promotion of healthy civil-military relations, which include civilian control of U.S. defense and national security policy.

As the secretary has said before, the role and use of the U.S. military must be clearly connected to the will of the American people. Civilian control of the military, and unity of department action in accordance with it, is vital to our success.

To that end, we are instilling discipline processes and governance structures in the defense enterprise. This includes the explicit use of bodies such as the Deputy's Management Action Group, also known as the DMAG, to advance the secretary's commitment to innovation and modernization.

Standing invitations to the DMAG have been extended to senior DOD personnel such as the secretaries of the military's departments, chiefs of the military services, combatant commanders, and OSD principal staff assistance.

I have also established subordinate governance forums on defense strategy and defense innovation, and will leverage existing bodies like the Nuclear Weapons Council to help drive civilian and uniformed leaders to build firm foundations for enduring change.

Through the deputy's newly created Workforce Council, we will bring the same vision and disciplined execution to talent management that we devote to weapons systems and budgets. A real, enduring, bipartisan consensus has emerged around the multidimensional challenge that Beijing presents.

Democrats and Republicans alike recognize that the Department of Defense should and must prioritize the PRC as the pacing challenge for the United States. As such, DOD should be confident that it will continue to receive the support required to sustain our edge.

As the department begins the congressionally mandated process of reviewing and revising its defense strategy, we must seek to ensure not simply that we have the resources we need, but also that our military concepts and capabilities can deter and, if needed, win against our most challenging rivals. We must not only succeed in the competition of ideas, but in the steadfastness of our execution.

Thank you all for allowing me the privilege of speaking with you today. I very much look forward to your questions.