When Army Lt. Col. Edward A. Silk realized that his

platoon wasn't going to put a dent in the enemy positions firing at them

in France during World War II, he went on a one-man rampage to take the

guns out himself. Miraculously, his mission succeeded. For his heroics,

he received the Medal of Honor.

Silk was born June 8, 1916, in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, to Irish

immigrants Michael and Mary Silk. He was the youngest of 11 children.

When Silk was 2, his father died in an accident at the local

Bethlehem Steel mill, according to the newspaper The Daily Herald out of

Everett, Washington. His mother tried to care for all 11 children on

her own, but she couldn't, so she eventually moved with her four

youngest to Illinois to live at Mooseheart Child City, a residential

child care community run by the Loyal Order of Moose, of which Silk's

father was part. Mooseheart provides children and families in need with

stability, support and education.

Silk did well at Mooseheart. According to the Moose organization, he

played football for the high school and chose to stay an extra year due

to job scarcity from the Depression so he could get training in

ornamental concrete work. After graduating in 1935, he attended St.

Bonaventure College in western New York for a time before eventually

dropping out to join the workforce.

In April 1941, months before the U.S. entered World War II, Silk

joined the Army Reserve. At some point he married his girlfriend,

Dorothy Weimer, and had a son named Jerry.

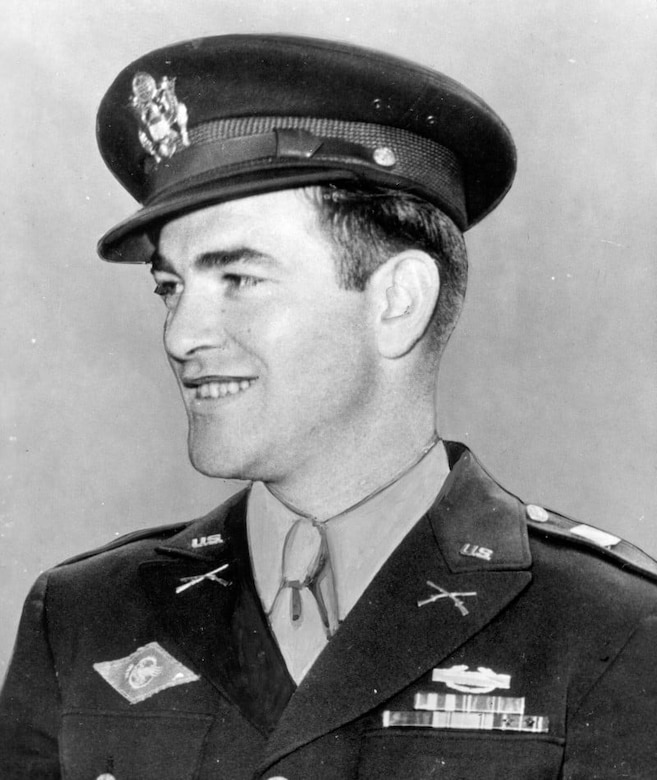

Silk was ordered to active duty Aug. 31, 1942. He earned a commission

at Fort Benning, Georgia, before being sent to France in October 1944

with the 398th Infantry, 100th Infantry Division. About two months

later, his brazen courage earned him the nation's highest medal for

valor.

On Nov. 23, 1944, then-1st Lt. Silk's battalion was tasked with seizing

high ground overlooking Moyenmoutier, France, ahead of a planned attack

to liberate the city. Silk was commanding a weapons platoon in Company E

that took the lead at dawn. By noon, they'd reached the edge of the

woods near St. Pravel, where scouts saw in the valley below an enemy

sentry standing guard outside a farmhouse.

Almost immediately, the scouting squad was pinned down by intense

gunfire coming from within the house. Silk's platoon returned fire, but

after about 15 minutes, there was no letting up in the enemy gunfire.

So, Silk decided to take matters into his own hands.

He ran 100 yards across an open field before taking shelter behind a

low stone wall directly in front of the farmhouse. After firing into the

door and windows with his carbine, Silk then vaulted over the wall

sheltering him and dashed another 50 yards through a hail of enemy

gunfire to the left side of the house. He then tossed a grenade through

an open window. The explosion that followed silenced the enemy machine

gun and killed its two gunners.

When Silk tried to move to the right side of the house, another enemy

machine gun began firing on him from a nearby woodshed. Summoning every

ounce of courage he had, Silk rushed that position head-on, dodging

direct fire to get close enough to throw more grenades, which destroyed

that gun and its gunners as well.

By that point, Silk had run out of grenades — but not fortitude. Silk

ran to the back side of the farmhouse, where he began to throw rocks

through the window, demanding the remaining enemy soldiers' surrender.

"Twelve Germans, overcome by his relentless assault and confused by his

unorthodox methods, gave up to the lone American," Silk's Medal of Honor

citation said.

Thanks to his decision to take on the burden of the attack alone,

Silk's battalion was able to continue its advance on Moyenmoutier and

eventually liberate the city.

Silk returned home in September 1945 as a hero. On Oct. 12, 1945, he

and 14 other deserving service members received the Medal of Honor from

President Harry S. Truman during a White House ceremony.

Silk remained in the Army after the war, working for a time while

still on active duty as a patient consultant for the Department of

Veterans Affairs. One of his last posts was with the 7822nd Station

Complement Unit in Stuttgart, Germany.

By 1952, Silk had risen to the rank of lieutenant colonel. He and his wife went on to have two more children, Judith and Daniel.

In December 1954, Silk took command of the ROTC unit at Canisius

College (now university) in Buffalo, New York, as a professor of

military science and tactics.

Sadly, about 10 months later, Silk fell critically ill due to

intestinal ulcers. He underwent at least three surgeries at a local

military hospital before succumbing to complications on Nov. 19, 1955.

He was only 39.

During his funeral services, the newspaper The Buffalo News reported

that 600 ROTC cadets from Canisius marched behind Silk's hearse for 3

miles to St. Joseph's Cathedral, where his services were held. Silk was

then buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

In 2004, Johnstown renamed a bridge in the hometown hero's honor. At

the time, his daughter told newspapers that her father was a strict

disciplinarian, but he was kind and had a great sense of humor.

This article is part of a weekly series called "Medal of

Honor Monday," in which we highlight one of the more than 3,500 Medal

of Honor recipients who have received the U.S. military's highest medal

for valor.