Sept. 11, 2025 |

It's been 73 years since a C-124 Globemaster II, carrying 52 military members, tragically crashed into Mount Gannett in the Chugach Mountains of eastern Alaska, 40 miles from its destination of Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson.

It's believed the crash created an avalanche that, in some places, caused debris to be covered in hundreds of feet of drifted snow. Because of extremely challenging conditions, recovery efforts were terminated after one week, leaving the service members and their memories frozen in time for six decades. Then, in 2012, a survival raft was discovered on the north-flowing Colony Glacier, roughly 12 miles from the original crash site, just above Lake George.

Since the discovery, members from numerous organizations have gathered every summer to search the glacier for more remains in Operation Colony Glacier, an effort to identify and bring home the men who perished. Among the organizations that are a part of the operation, the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System plays a crucial role.

For the past eight years, Carlos Colon, Armed Forces Medical Examiner System medicolegal death investigator, has been a part of the operation.

"So, 2017 was the first time I flew onto Colony Glacier," Colon said. "That trip was basically a site visit where we assessed a number of things. After that trip, we started discussions about the benefits of having somebody from AFMES being involved in the search and recovery."

Colon was chosen to participate in the operation not only as subject matter expert on the identification and collection of remains, but also because of his background in search and recovery.

"As medicolegal investigators we have training in search and recovery and we do response to aircraft mishaps," Colon said. "A lot of our aircraft mishaps have highly fragmented remains. It can be difficult to discern those remains from things like rocks or wood, especially when they have been exposed to extreme elements for so long. By the time I went to Colony Glacier, I had already seen remains being sampled here at AFMES for two years, so I was already very familiar with what to look for out there."

Along with the type of knowledge that investigators like Colon bring, comes the continuity that is essential to an operation like Colony Glacier.

"Most people on the team are only there for one year," Colon said. "Usually, the officers in charge of ground forces and the commander from the Air Force Mortuary Affairs Operations will have been on the team two years at max. So, we're [medicolegal investigators] really bringing that knowledge of not only what human remains look like, but also bringing insight on how remains are triaged, sampled and tested here at AFMES. It's extremely beneficial for the people on the ground to be speaking the same language as the people doing the sampling, and the DNA folks actually doing the testing because we're always thinking, 'how can we maximize our chances of getting new identifications?' Whether that be advising on refocusing efforts to find more osseous material, teeth or soft tissue, or concentrating on other locations that have samples we know will likely produce a good DNA profile. We are always thinking more about the identifications and the forensic sciences behind the recovery."

The glacier, however, presents a special set of challenges that make traditional recovery methods extremely difficult.

"With the glacier, everything is ephemeral," Colon said. "Things shift on the glacier and the glacier itself moves; it's basically a moving river of ice. We found pretty quickly that a lot of prior methods being used, which are typically really thorough and great for documenting a scene, documenting a recovery and knowing exactly where everything was found, were not working well and it's because those traditional techniques are for sites that are static."

New methods had to be employed along with a different mindset of how to navigate the recovery in this desolate and ever-changing landscape.

"Together, AFMAO and AFMES, realized that there has to be a little bit more urgency," Colon said. "AFMAO is primarily concerned with finding as many personal effects as possible and for AFMES, we want to get as many remains and samples as possible. So, we started refocusing our priorities on getting as many samples from different parts of the glacier with as much variety as possible, to hopefully increase the chances of making new identifications."

This forensic approach has helped shape ongoing recovery efforts; everything from training, managing timelines and resources and bringing a new perspective to the operation as a whole.

"Before we even go out, I'll provide necessary training to our folks," Colon said. "I'll give presentations, show them what things look like, inform about what happens at AFMES post-recovery, how remains get to Dover, how our mortuary affairs specialists, medical examiners and medicolegal death investigators triage, photograph, sample and submit to DNA. I also provide summaries on adipocere, mummification, skeletonization and patterns of decomposition that are more relevant to what we see on the glacier."

This methodology means that time and resources are amplified to the fullest extent.

"We've lost a lot of the glacier," Colon explained. "It's very dynamic compared to a standard anthropological site, and the way we're operating now is more focused on knowing that we have limited amount of time and resources. We only have four weeks each year to conduct this recovery so we're always trying to get the most out of the time we have left with the debris field, because it's moving further down-glacier. Our goal is always to be more conscious of how we spend our time. We know if we are not efficient with our resources at the site, it will lead to our medical examiners and DNA technicians' time not being used properly back at AFMES. Having said that, every year our lab gets better, there is always a new process or new technology, so in the field we try and adjust and be more efficient and better every year as well."

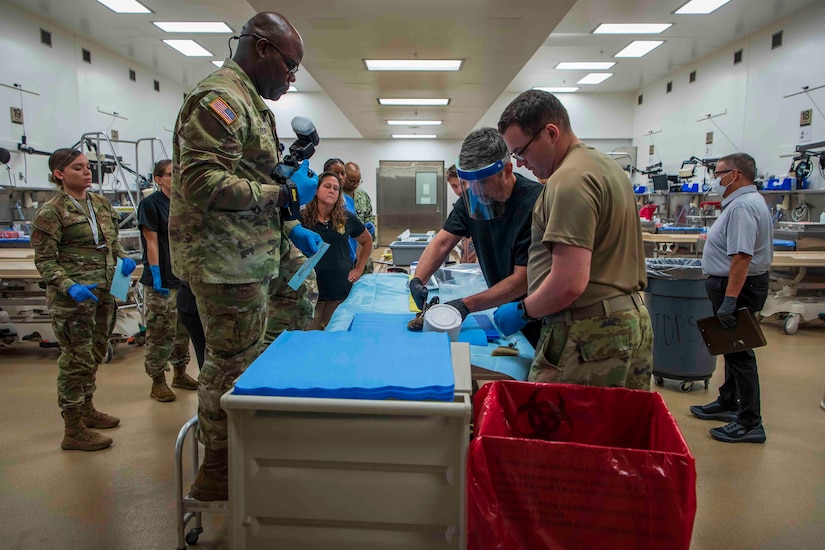

The samples collected in the field are sent back to the AFMES where the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory will compare extracted DNA against a robust database of family member references that have been gathered over decades. Family members can donate DNA samples through requesting a sample kit or attending a family member update or an annual government briefing hosted by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency.

To date, 50 of the 52 fallen members have been identified. The 50th identification was made just this year.

Army Air Forces Airman 3rd Class James Ronald Kimball, a flight steward, a career field similar to a modern-day crew chief, was assigned as a crew member on the flight.

"This was a big deal," Colon said. "Kimball was the one that we were told we had very little shot of identifying because he had no family member DNA reference; he was adopted with no children. But what he did have was a very specific fingerprint pattern on his right thumb and what looks like a burn scar on his right index finger. Fortunately, we knew this because of the fingerprints that were on file."

Even more fortunate, his personnel files survived a devastating 1973 fire, which destroyed between 16-18 million official military personnel files in the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis.

"During our second trip out there, I received a radio call from one of the team members, [Air Force 1st Lt. Mason] Tarkenton," Colon said. "They were searching a smaller debris field, that was not previously found, in the upper limits of our established area. He said 'Carlos, I found a right hand up here near what looks like a crew jacket,' and I was like 'there is no way,' because Kimball was the last crew member that was still missing. The hand was so well preserved that, once I got back to the morgue, I was able to send pictures to our fingerprint expert at the FBI, and within six hours they were able to make a positive ID. That was exciting; it was the fastest identification we've made."

Prior to the AFMES' involvement, 585 specimens were recovered for sampling over a period of five years. In the first five years of the AFMES' involvement, 4,520 specimens were recovered, with a total of 6,528 specimens recovered since 2017. This year alone, 373 samples were collected and accessioned for DNA testing in a record five days. Each year the team becomes more exact in carrying out this mission, as they strive to bring closure to families who have had to wait so long.

"We've had really great collaboration with our partners at AFMAO," Colon said. "We always go out there as Team Dover, and ultimately, we want the same exact thing, which is for all of the members on board to be accounted for."