Oct. 2, 2020 | , DOD News

The Army communications specialist had no idea what she was getting into when her battalion commander asked her if she wanted to go to the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York.

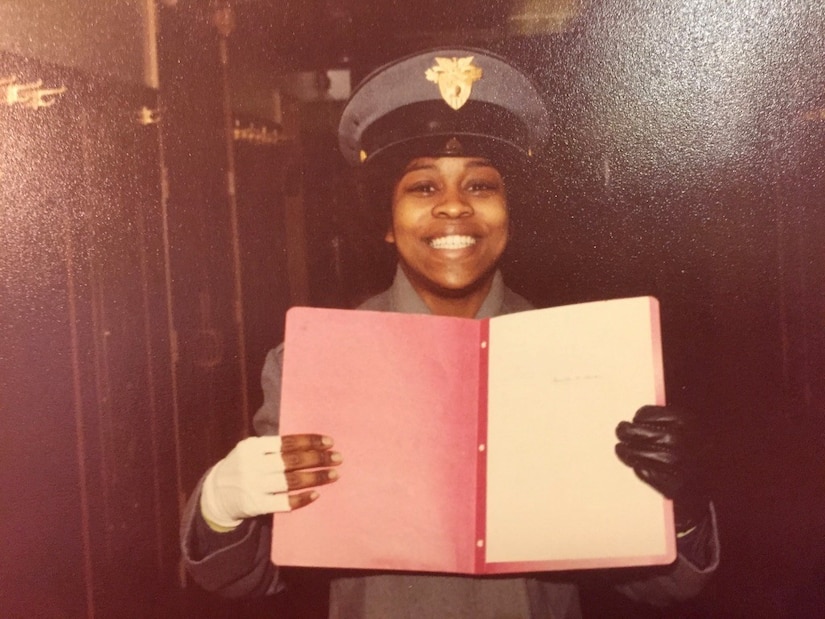

Stationed at Fort Polk, Louisiana, in 1976, now-retired Army Maj. Pat Locke had never heard of West Point, she said. But when she learned she could get a college degree, the Detroit-born woman packed her belongings in a duffel bag and drove to the school the following day.

She laughs now, remembering when she told herself, '''How bad could it be?'''

Little did she know she would become a member of a college that separated people into ''males,'' and ''non-males.'' Her class started with 119 women, and 62 graduated.

Locke also became the first Black woman to become a Military Academy graduate by order of merit in her 1980 class. Today, graduates are listed alphabetically, rather than by merit, she explained.

''It wasn't much different from being in the Army, but at Fort Polk, Louisiana, I was around a lot of people who looked like me. When I got to the academy, there were very few people who looked like me. That was the first rude awakening I had when I got there,'' Locke said.

She said that being from Detroit, she spoke differently and had to fight a language barrier. ''Very few people could understand what I was saying, so that was a problem for me,'' she said. ''That was the biggest thing I had to overcome.''

And being at what had been an all-white-male school, she had to make an adjustment check. ''I had to check my attitude because I said that no matter what, I'm not leaving,'' she said.

Locke said she was inspired to go to West Point by the battalion commander who first approached her about West Point, and that she probably would not have pursued a college degree otherwise.

In her second year at the academy, she got help from a tactical officer who was a native New Yorker, to whom she could relate, she said. ''That's when I got a little more confidence in myself and I'd learned to speak a little bit better,'' she recalled.

Locke joked about probably forgetting any math she'd learned in high school, and she said her math professors pushed her. ''I felt like I learned five years of math in one year,'' she said. ''I passed, and a lot of people were getting kicked out left and right.'' Today, she tutors math for high school students who aspire to go to the Military Academy and are preparing for their SAT and ACT exams.

But in addition to teaching math for college entrance exams, Locke shares her wealth of experience with other young women coming into the academy. She currently volunteers as a member of the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the services, or DACOWITS, as well as recruits for the Military Academy as an admissions field representative.

''Most don't come [into the academy] as a fully-formed leader,'' she tells them. ''You come in with the raw materials of being a great leader, but you've got to shape it, pound it, knead it, bake it and sharpen it. And sometimes that hurts.''

A sense of patience is also required at the academy, she tells them. ''You are there to shape yourself into the best leader of character that you can be,'' she says.

''Everybody has to learn ‘how to cooperate in order to graduate','' Locke said. ''That's what you learn at the academy, and you take that with you for the rest of your life. I cherish the times I can tell people about the academy and what they're going to get from it. I think all the services are better because we have women in them.''

Read the stories of other women who attended military academies.

No comments:

Post a Comment