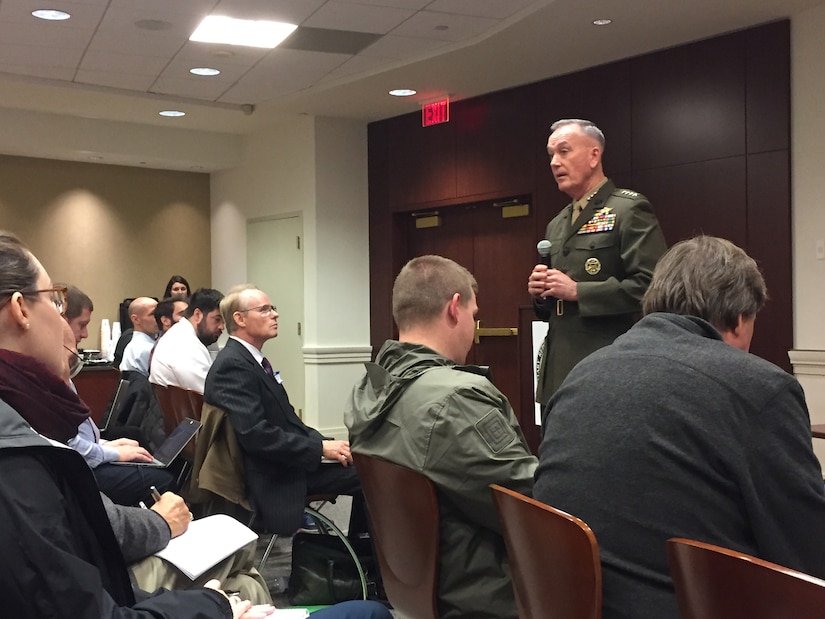

By Jim Garamone, Defense.gov

ARLINGTON, Va. -- t is a dangerous and unpredictable time,

and the United States must reverse any erosion in its military capabilities and

capacities, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff said at the Military

Reporters and Editors conference here Oct. 26.

Marine Corps Gen. Joe Dunford is confident the U.S. military

can protect the homeland and fulfill its alliance commitments today, but he must

also look at the long-term competitive advantage and that causes concern.

He said the competitive advantage the U.S. military had a

decade ago has eroded. “This is why our focus is very much on making sure we

get the right balance between today’s capabilities and tomorrow’s capabilities

so we can maintain that competitive advantage,” Dunford said.

Strategic Alliances Provide Strength

The greatest advantage the United States has – the center of

gravity, he said – is the system of alliances and partners America maintains

around the world.

“That is what I would describe as our strategic source of

strength,” he said.

This network is at the heart of the U.S. defense and

security strategy, Dunford said. “We really revalidated, I think, what our

threat assessors have known for many years, is that that network of allies and

partners is truly unique to the United States of America and it is truly

something that makes us different,” the general said.

A related aspect is the U.S. ability to project and maintain

power “when and where necessary to advance our national interests,” Dunford

said.

“We have had a competitive advantage on being able to go

virtually any place in the world,” he said, “and deliver the men and women and

materiel and equipment, and put it together in that capability and be able to

accomplish the mission.”

This is what is at the heart of great power competition, the

general said. “When Russia and China look at us, I think they also recognize

that it is our network of allies and partners that makes us strong,” he said.

Challenges Posed by Russia, China

Broadly, Russia is doing what it can to undermine the North

Atlantic Alliance and China is doing what it can to separate the United States

from its Pacific allies. Strategically, Russia and China are working to sow

doubt about the United States’ commitment to allies. Operationally, these two

countries are developing capabilities to counter the U.S. advantages. These are

the seeds to the anti-access/area denial capabilities the countries are

developing. “I prefer to look at this problem less as them defending against us

and more as what we need to do to assure our ability to project power where

necessary to advance our interests,” Dunford said.

These are real threats and include maritime capabilities,

offensive cyber capabilities, electromagnetic spectrum, anti-space capabilities

and modernization of the nuclear enterprise and strike capabilities. These

capabilities are aimed at hitting areas of vulnerability in the American

military or in striking at the seams between the warfighting domains.

“In order for us to be successful as the U.S. military,

we’ve got to be able to project power to an area … and then once we’re there

we’ve got to be able to freely maneuver across all domains … sea, air, land,

space, and cyberspace,” the chairman said.

This requires a more flexible strategy, he said. During the

Cold War, the existential threat to the United States emanated from the Soviet

Union and strategy concentrated on that. Twenty years ago, this was different.

The National Security Strategy of 1998 didn’t address nations threatening the

U.S. homeland.

“To the extent that we talked about terrorism in 1998, we

talked about the possible linkage between terrorism and weapons of mass

destruction,” Dunford said. “For the most part, what we talked about were

regional challenges that could be addressed regionally with coherent action

within a region, not transregional challenges.”

Different Threats

Transregional threats are a fact of life today and must be

addressed, the general said. “What I’m suggesting to you, is in addition to the

competitive advantage having eroded, the character of war has fundamentally

changed in my regard in two ways,” he said. “Number one, I believe any conflict

… is going to be transregional –

meaning, it’s going to cut across multiple geographic areas, and in our case,

multiple combatant commanders.”

Another characteristic of the character of war today is

speed and speed of change, he said. “If you’re uncomfortable with change,

you’re going to be very uncomfortable being involved in information technology

today,” the general said. “And if you’re uncomfortable with change, you’re

going to be uncomfortable with the profession of arms today because of the pace

of change. It’s virtually every aspect of our profession is changing at a rate

that far exceeds any other time in my career.”

He noted that when he entered the military in 1977, the

tactics he used with his first platoon would have been familiar to veterans of

World War II or the Korean War. The equipment and tactics really hadn’t changed

much in 40 years.

But take a lieutenant from 2000 and put that person in a

platoon “and there’s virtually nothing in that organization that hasn’t changed

in the past 16 or 17 years,” Dunford said. “This has profound impacts on our

equipment, our training, the education of our people.”

This leads, he said, to the necessity of global integration.

“When we think about the employment of the U.S. military, number one we’ve got

to be informed by the fact that we have great power competition and we’re going

to have to address that globally,” he said.

The Russian challenge is not isolated to the plains of

Europe. It is a global one, he said.

“China is a global challenge” as well, Dunford added.

Global Context

American plans have historically zeroed-in on a specific

geographic area as a contingency, the general said. “Our development of plans

is more about the process of planning and developing a common understanding and

having the flexibility to deal with the problem as it arises than it is with a

predictable tool that assumes things will unfold a certain way in a

contingency,” he said. “So we’ve had to change our planning from a focus on a

narrow geographic area to the development of global campaign plans that actually

look at these problem sets in a global context. When we think about contingency

planning, we have to think about contingencies that might unfold in a global

context.”

This has profound implications for resource allocation,

Dunford said. Forces are a limited resource and must be parceled out with the

global environment in mind. “The way we prioritize and allocate forces has kind

of changed from a bottom-up to a top-down process as a result of focusing on

the strategy with an inventory that is not what it was relative to the

challenges we faced back in the 1990s,” he said.

In the past, the defense secretary’s means of establishing

priorities came through total obligation authority. The secretary would assign

a portion of the budget to each one of the service departments and the services

would develop capabilities informed by general standards of interoperability.

At the time, this meant the American military had sufficient forces that would

allow it to maintain a competitive advantage.

“Because the competitive advantage has eroded, in my

judgment, the secretary is going to have to be much more focused on the

guidance he gives,” Dunford said. “He not only has to prioritize the allocation

of resources as we execute the budget, but he’s got to five, seven or 10 years

before that, make sure that the collective efforts of the services to develop

the capabilities that we need tomorrow are going to result in us having a

competitive advantage on the backside.”

This fundamentally changes the force development/force

design process, he said. “This is not changing because of a change in

personalities. It’s not changing because different leaders are in place,” the

general said. “It’s changing because the character of war has changed, the

strategic environment … within which we are operating today and expect to be

operating in five to seven years from now, will change. Frankly, were we to not

change the fundamental processes that we have in place inside the department,

we would not be able to maintain a competitive advantage five or seven years

from now.”

No comments:

Post a Comment