By Army Col. Richard Goldenberg New York National Guard

SARATOGA SPRINGS, N.Y., Feb. 1, 2018 — During World War I,

when African-American National Guard soldiers of New York’s 15th Infantry

Regiment arrived in France in December 1917, they expected to conduct combat

training and enter the trenches of the western front right away to fight the

enemy.

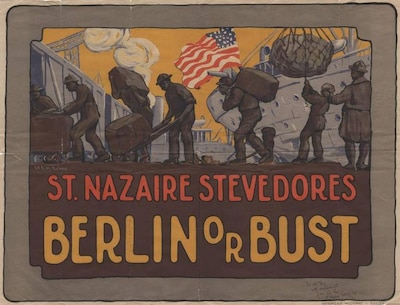

However, at first, the African-American troops were ordered

to unload supply ships at the docks for their first months in France, joining

the mass of supply troops known as stevedores, working long hours in the port

at St. Nazaire.

More than 380,000 African-Americans served in the Army

during World War I, according to the National Archives. About 200,000 were sent

to Europe. But more than half of those who deployed were assigned to labor and

stevedore battalions. These troops performed essential duties for the American

Expeditionary Force, building roads, bridges and trenches in support of the front-line

battles.

Preparing Docks, Railway Lines

In St. Nazaire, the New York National Guard soldiers learned

they would work to prepare the docks and railway lines to be a major port of

entry for the hundreds of thousands of forces yet to arrive in France. The

African-American regiment was a quick and easy source of labor, according to

author Stephen Harris in his 2003 book "Harlem’s Hell Fighters."

“First, [Army Gen. John J.] Pershing would have a source of

cheap labor,” Harris wrote. “Second, he wouldn’t have to worry about what to do

with black soldiers, particularly when he might have to mix them in with white

troops.”

But the 15th Regiment’s soldiers had not signed up for

labor. They were committed to fighting the Germans and winning the war.

“They had no place to put the regiment,” said infantry Capt.

Hamilton Fish, according to the Harris book. “They weren’t going to put us in a

white division, not in 1917, anyway; so our troops were sent in to the supply

and services as laborers to lay railroad tracks. This naturally upset our men

tremendously.”

Regimental Commander Fights for Troops

The regiment’s best advocate to get into the fight was their

commander, Col. William Hayward.

“It was time for us to try to do something towards

extricating ourselves from the dirty mess of pick-swinging and wheel barrel

trundling that we were in,” Hayward had said to Capt. Arthur Little, commander

of the regimental band, according to Jeffrey Sammons in his 2014 book

"Harlem’s Rattlers and the Great War."

“We had come to France as combat troops, and, apparently, we

were in danger of becoming labor troops,” Hayward said.

Hayward argued his case in a letter to Pershing, outlining

the regiment’s mobilization and training, and followed up immediately with a

personal visit to Pershing’s headquarters.

Band Helps Sway Opinion

He would bring with him the regiment’s most formidable

weapon in swaying opinion: the regimental band, lauded as one of the finest in

the entire Expeditionary Force.

While the regiment literally laid the tracks for the arrival

of the 2 million troops deploying to France, the regimental band toured the

region, performing for French and American audiences at rest centers and

hospitals. The 369th Band was unlike any other performance audiences had seen

or heard before, Harris noted. The regimental band is credited with introducing

jazz music to France during the war.

The military band would frequently perform a French march,

followed by traditional band scores such as John Philip Sousa’s “Stars and

Stripes Forever.”

“And then came the fireworks,” said Sgt. Noble Sissle, band

vocalist and organizer, in the Harris account, as the 369th Band would play as

if they were in a jazz club back in Harlem.

After some three months of labor constructing nearby

railways to move supplies forward, the regiment’s soldiers learned that they

had orders to join the French 16th Division for three weeks of combat training.

Heading for the Front

They also learned they had a new regimental number as the

now-renamed 369th Infantry Regiment. Not that it mattered much to the soldiers;

they still carried their nickname from New York, the Black Rattlers, and

carried their regimental flag of the 15th New York Infantry everywhere they

went in France.

While the 369th Infantry would become part of the U.S.

Army’s 92nd Infantry Division, it would be assigned to fight with French

forces. This solved the dilemma for Pershing and the American Expeditionary

Forces of what to do with the African-American troops.

The black troops would see combat, but alongside French

forces, who were already accustomed to the many races and ethnicities already

serving in the ranks of their colonial troops.

“The French army instructors literally welcomed their

African-American trainees as comrades in arms,” Sammons wrote. “To the

pragmatic French army instructors, the soldiers were Americans, black

Americans, to be trained for combat within their ranks. The trainees clearly

excelled at their tasks.”

After learning valuable lessons in trench warfare from their

French partners, the soldiers of the 369th finally had their chance to prove

their worth as combat troops when they entered the front lines, holding their

line against the last German spring offensive near Chateau-Thierry.

Acclaimed Fighters

Their value was not lost on the French, and the regiment

continued to fight alongside French forces, participating in the Aisne-Marne

counteroffensive in the summer of 1918 alongside the French 162st Infantry

Division.

The Hell Fighters from Harlem had come into their own, in

spite of their difficult start.

The regiment would go on to prove itself in combat

operations throughout the rest of the war, receiving France’s highest military

honor, the Croix de Guerre, for its unit actions alongside some 171 individual

decorations for heroism.

During the World War I centennial observance, the New York

National Guard and New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs will

issue press releases noting key dates that affected New Yorkers, based on

information and artifacts provided by the New York State Military Museum here.

More than 400,000 New Yorkers served in the military during

World War I, more than any other state.

No comments:

Post a Comment